General Motors may already be grooming its next chief executive, and he comes straight out of the EV and autonomy world.

Sterling Anderson—a former Tesla executive and cofounder of autonomous trucking firm Aurora Innovation—joined GM in June as chief product officer. According to a Bloomberg report, he’s now a prime candidate to eventually succeed CEO Mary Barra, 63, if he can deliver on a very aggressive mandate.

When GM hired him, people familiar with the deal say the understanding was simple:

“If Anderson can bring cutting‑edge software and self‑driving capability into GM’s lineup and make EVs profitable, he’s got a real shot at the top job.”

A GM spokesperson is downplaying the chatter, calling any talk of his future role “premature and speculative.” But the job description GM has handed Anderson tells you everything you need to know: Beef up computing power and software in GM vehicles, Push forward “eyes‑off” driving (true hands‑free autonomy), Build out subscription features that generate recurring revenue, Make GM’s electric lineup profitable, not just impressive on paper.

The stuff that’ll separate winners from losers over the next decade. Anderson’s résumé fits the moment. At Tesla, he led both the Model X and Autopilot programs. At Aurora, he lived and breathed commercial autonomy. But moving fast in Silicon Valley is very different from re‑wiring a century‑old Detroit giant.

GM’s recent record shows what he’s up against: It shut down its Cruise robotaxi operations after a serious crash and regulatory backlash, Waymo has been expanding robotaxi service while GM has been regrouping, GM’s software game lags behind Tesla and other “born‑digital” rivals, The Chevy Blazer EV struggled with early software issues at launch, GM has had trouble keeping top AI and software talent; key leaders have left recently.

Anderson told Bloomberg he knows he’s walking a tightrope and is trying to operate “surgically”, “You simply cannot afford to break a company and hope to pull the pieces back together at a company like General Motors,” he said. If he pulls it off, he could become the face of GM’s next era. If he can’t, it’s another reminder of how hard it is to drag a legacy automaker into a software‑first future.

After Years of EV Hype, U.S. Sales Finally Dip

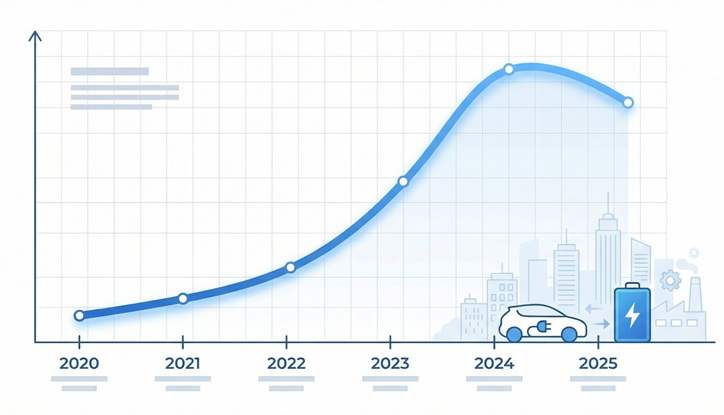

For years, you could count on one thing: U.S. EV sales were going up—fast. That streak just ended. New estimates from Cox Automotive show that after a record run, EV sales in 2025 are expected to fall slightly compared with last year.

Shoppers rushed to buy EVs in Q3 to grab federal tax credits before they expired on September 30, That produced a record third quarter, Once the incentive window closed, demand dropped hard in Q4.

Q4 2025 EV sales: ~230,000 vehicles

- Down 46% from Q3

- Down 37% from Q4 a year earlier

EV market share in Q4: down to 5.7% of all U.S. new-car sales, Cox expects a 2.1% decline in EV sales:

- 2024: about 1.3 million EVs sold (a record)

- 2025 (projected): roughly 1.275 million

Cox’s Stephanie Valdez Streaty summed it up on a call this week: “The year was defined by extreme volatility driven by policy changes.”

U.S. EV Sales Trend (Cox Automotive, Approximate)

| Year | Estimated EV Sales (U.S.) | What Changed |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | ~250,000 | Early adopters, limited models |

| 2021 | ~488,000 | More choices, growing awareness |

| 2022 | ~810,000 | Mainstream brands lean into EVs |

| 2023 | ~1.2 million | Big growth despite early headwinds |

| 2024 | ~1.3 million | Record year, up >7% vs. 2023 |

| 2025 | ~1.275 million (projected) | First dip, tax-credit hangover hits |

So no, EVs aren’t “dead.” But the era of automatic double‑digit growth is over—at least for now.

Valdez Streaty expects more choppy waters ahead:“We expect continued market adjustment, as consumers and dealers recalibrate to the new pricing reality without federal incentives,” she said. automakers can’t rely on Washington to move metal. They’ll have to sharpen pricing, improve charging, and build EVs people actually want—on their own merits.

A $1.1 Billion SPAC and a 2027 Target

You’d think with all the bad vibes around EVs and SPACs, a battery startup might lay low for a while. Factorial has other ideas. The Massachusetts‑based solid‑state battery company announced Thursday that it plans to go public via a SPAC merger next year. The deal: Values Factorial at about $1.1 billion, Would bring in roughly $100 million in fresh funding.

CEO Siyu Huang told The New York Times this is an “inflection point” for the company’s commercialization push. The goal: use that money to bring solid‑state batteries to the auto market by 2027.

On paper, solid‑state tech is the EV holy grail: Better safety (less fire risk), Higher energy density (more range in the same space), Faster charging. In reality, nobody has cracked mass production at car scale yet. But Factorial is at least getting its cells into real hardware: Mercedes‑Benz has tested Factorial cells in a prototype EQS sedan, Stellantis plans to use Factorial tech in some Dodge Charger Daytona demonstrator vehicles in 2026.

Lithium‑ion batteries—the ones in today’s EVs—keep getting Cheaper, More energy dense, More durable. Every year they improve, the bar for a “revolutionary” solid‑state product gets higher.

So does the world need a solid‑state moonshot? Or will ever‑better lithium‑ion be “good enough” for most drivers?

Factorial is betting that carmakers—especially premium brands—will pay for a clear step up in range, safety, and charge time. If it can hit its 2027 target, it may have a shot at being more than a science‑fair project with a stock ticker. If not, it risks becoming another cautionary tale from the first big wave of EV‑tech SPACs.

GM is trying to bring a Tesla‑trained outsider into the driver’s seat. EV sales are finally hitting a plateau after years of straight‑up growth. And battery startups are still swinging for the fences with solid‑state tech. The future of transportation isn’t arriving in a straight line. It’s coming in lurches—one leadership bet, one sales report, and one high‑risk battery play at a time.

Related Post