Ford Motor Co. has dropped more than cash on Louisville — it’s dropped a challenge to the way cars are built. The company’s newly announced $2 billion investment in its Kentucky assembly operations isn’t just more tooling or another product line. It’s a deliberate attempt to reinvent manufacturing with a cheaper, faster way to produce electric vehicles — and to do it at a scale that could support as many as eight different nameplates.

That’s the payoff Ford is pitching. The risk is real: CEO Jim Farley and his leadership team now carry the responsibility of turning a skunkworks experiment into reliable, high-volume production without a major quality hiccup. The stakes are high because the company isn’t promising incremental change. It’s promising a new assembly concept — an “assembly tree” that, according to Ford, tosses the traditional moving assembly line in favor of parallel sub-assembly streams designed to cut time and complexity.

“We have all lived through far too many ‘good college tries’ by Detroit automakers to make affordable vehicles that ends up with idled plants, layoffs and uncertainty,” Farley said. “So, this had to be a strong, sustainable and profitable business. From Day 1, we knew there was no incremental path to success. We empowered a tiny skunkworks team three time zones away from Detroit. We tore up the moving assembly line concept and designed a better one.”

Ford says the first vehicle off the line will be a midsize, four‑door electric pickup — billed as the company’s bid at an affordable EV — slated to launch in 2027 with a target price of about $30,000. That kind of figure, if real and realized, would shake up the market by bringing an EV into price territory familiar to mainstream buyers. Ford is calling it a “Model T moment,” a bold label that ties ambition to a historic model of mass‑market disruption.

But ambition doesn’t erase execution risk. Investors have been wary: Ford shares have been stuck in a relatively low trading band since 2022, and the market won’t forgive missteps easily. There’s also a practical question hanging over the project: will buyers embrace an affordable EV in a market shaped by incentives, charging availability, and evolving preferences? Ford’s gamble rests on answering that “yes.”

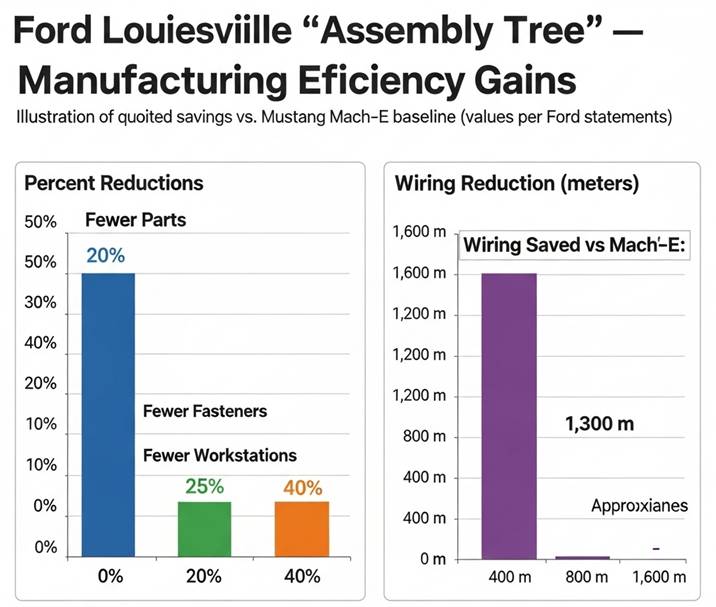

The assembly tree idea is more than a manufacturing novelty. Ford is aiming to shave parts counts, simplify wiring and cut the number of workstations on the line — efficiencies that translate directly into lower costs. If it works, Ford could produce multiple vehicle types off the same streamlined system and at lower per‑unit costs. That makes the Louisville plan less about a single truck and more about a new production playbook for the company.

And the timing matters. Automakers everywhere are under pressure to lower EV costs while expanding range, charging convenience and reliability. For Ford, which has had its share of hits and stumbles during the EV transition, this is an attempt to reassert control over both product and price.

The Louisville announcement arrives against broader industry shifts. News that China’s CATL is idling one of the world’s largest lithium mining operations has pushed lithium prices higher and given a lift to lithium producers’ share prices. Commodity shocks like this can complicate Ford’s cost calculus: even the best production strategy can be undone by spikes in raw‑material costs.

There’s also a competitive dimension. Ford’s “Model T” rhetoric aims to apply pressure across the industry — making EVs not just the province of luxury buyers or early adopters, but something that pocketbooks can handle. If Ford manages to deliver a $30,000 midsize electric pickup that’s safe, functional and appealing, rivals will have to respond.

Execution will be the key metric. A successful outcome looks like this: a stable production ramp, strong quality scores, profitable unit economics, and a product that finds a ready buyer base. A misstep could mean plant slowdowns, warranty headaches, and the kind of reputational damage that’s hard to reverse.

Ford’s messaging recognizes that danger. Farley’s comments about avoiding “idled plants, layoffs and uncertainty” read like a vow not to repeat the industry’s past mistakes. But words don’t build batteries, weld seams or debug software at scale. The proof will be in the trucks rolling off the new assembly tree and into customers’ hands — and whether those customers still want them when 2027 arrives.

The Louisville plan is a bold stroke. It’s also a reminder that the transition to EVs is as much a manufacturing challenge as it is an engineering or marketing one. Ford is betting billions on a new way to make cars. For shareholders, workers and buyers, it’s a promise that will need to be kept — and fast.

Related Post